Find more about:

- the inside of the instrument

- the outside of the instrument

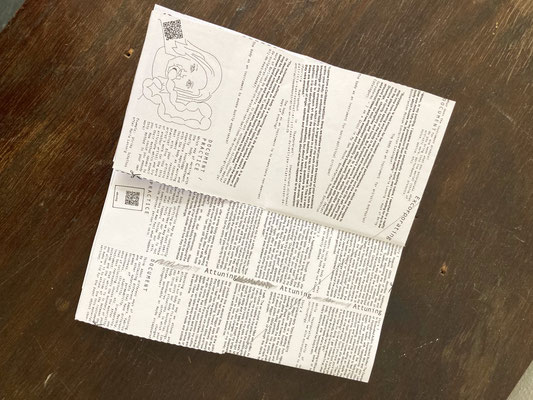

- attuning the instrument

What comes to mind if you think about a research instrument? What elements should it have? What should it feel like? Where would you take it?

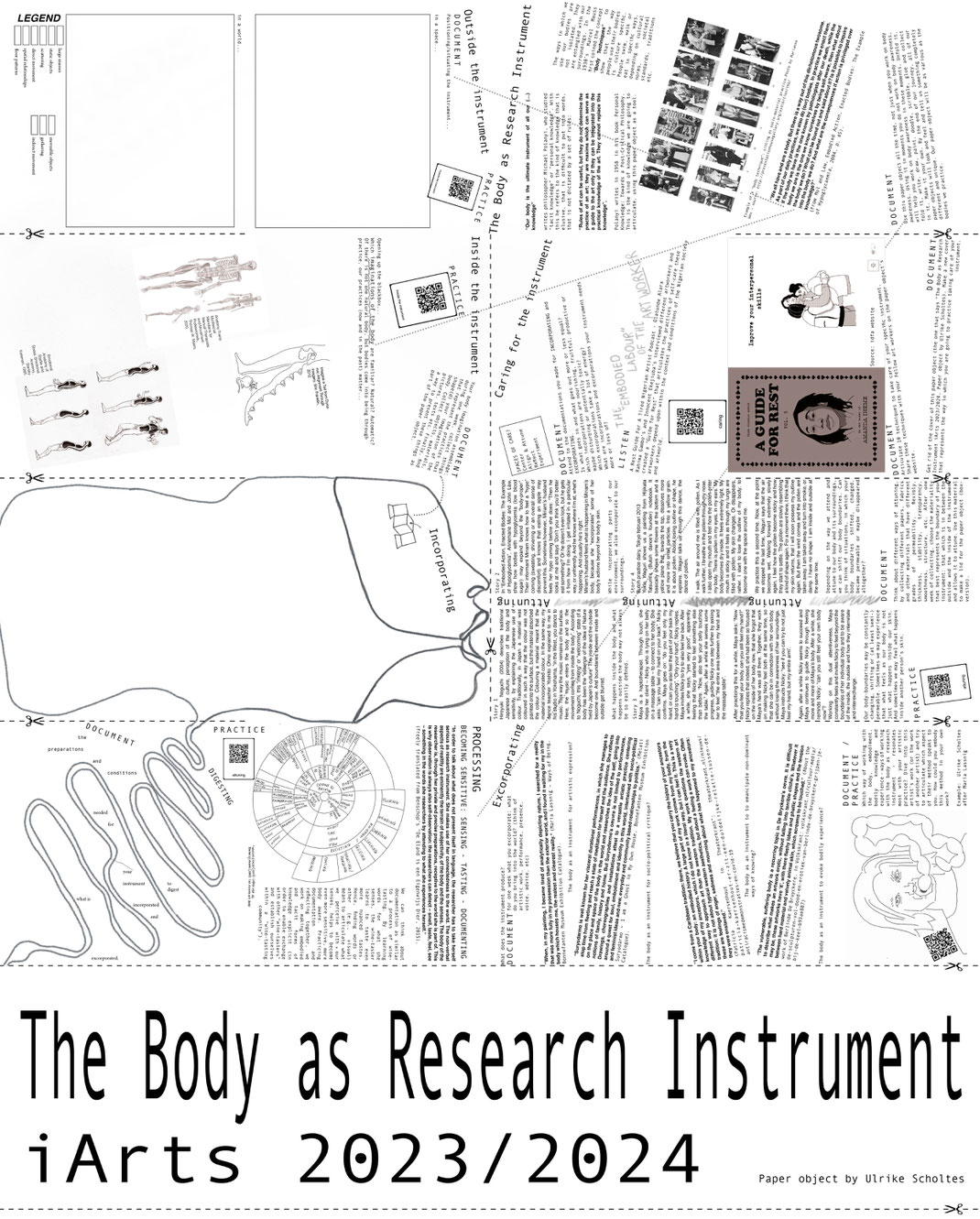

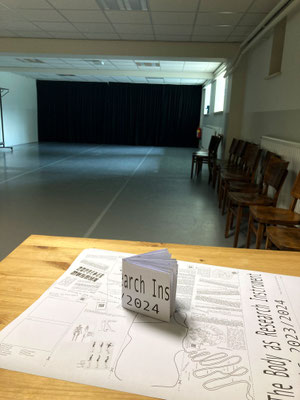

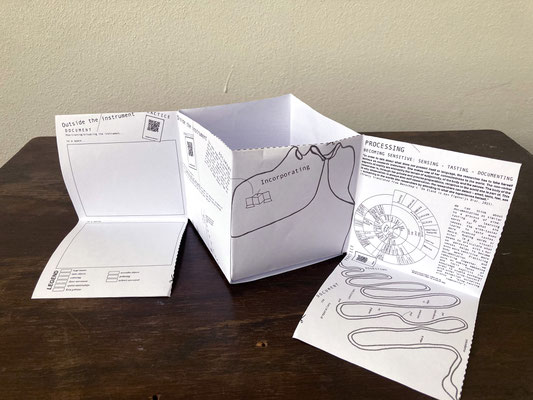

During the next couple of months, this paper object will represent your body as a research instrument. As time goes by, you will adapt this paper object in your own way, so that it functions more and more as a representation of your particular body as a research instrument

Your body as a research instrument: this imagination is meant to be metaphorical. Seeing your body as a research instrument is not meant as a way to define or conceptualise your body. Of course, your body is much more than “instrumental”. The metaphor functions as a thought-experiment. It invites you to become aware of your body within the context of your artistic practice. It allows you to reflect on your work in different terms, through a different language and other imaginations than you usually do, which fosters new insights in the way you work as artist.

“Our body is the ultimate instrument of all our (…) knowledge” writes philosopher Michael Polanyi, who studied “tacit knowledge” or “personal knowledge”. With this he refers to the kind of knowledge that is elusive, that is difficult to put into words, that is not dictated by a set of rules: “Rules of art can be useful, but they do not determine the practice of an art; they are maxims which can serve as a guide to the art only if they can be integrated into the practical knowledge of the art. They cannot replace this knowledge”, Polanyi writes in 1958 in his book Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. This is the kind of knowledge we are going to articulate, using this paper object as a tool.

We will work with the metaphor in relation to our body. As a practitioner and researcher, I work on emancipating practices that produce or enhance body awareness. My aim is to grant “body awareness” credits as a form of knowledge. Other than having it function in contexts in which the body awareness is instrumental in rather obvious ways, such as in therapeutic practices (practices that are meant to heal the body and/or mind) or performative practice in which the body plays an obvious role (such as dance, theatre, singing etc), I argue that body awareness plays an important role in artistic practices and research practices as well. Our bodies are not only always there. Through our bodies we engage with the world, they allow us to sense, register and attune to our surroundings, be present and move through spaces, incorporate and process information, and to be expressive and communicate with others. The ways in which we use our bodies are not isolated. They are entangled with our surroundings.

In the 1930’s Marcel Mauss first coined the concept “Body Techniques” to show that the way people use their bodies is culture specific. People swim, walk or eat in specific ways, depending on cultural norms, societal standards, traditions etc. The work of Annemarie Mol and others after her – me amongst others – builds on this idea that bodies are entangled with their socio-material surroundings. As Mol explains, some foreground the body we have. This is an “objective body”: a body that can be dissected into parts by naturalists, for instance. For others, this does not cover what the body is. Phenomenologists, for instance, foreground the body we are. This is a subjective body through which we experience the world. However, priotizing researching the body “in practices” over “knowing the body” Mol adds another body to the equation: the body we do!

“We all have and are a body. But there is a way out of this dichotomous twosome. As part of our daily practices, we also do (our) bodies. In practice we enact them. If the body we have is the one known by pathologists after our death, while the body we are is the one we know ourselves by being self-aware, then what about the body we do? What can be found out and said about it? Is it possible to inquire into the body we do? And what are the consequences if action is privileged over knowledge?”

(from Mol and Law, Embodied Action, Enacted Bodies: The Example of Hypoglycaemia, 2004, p. 45).

We will be inquiring the body we do when we practice artistic research. As a (future interdisciplinary) artist, one develops a specific practice; a practice that is specific to one’s individual work, consisting of research, methodology, style, materials, social relations, performances, presentations, expressions and so on. These practices are not isolated from our surroundings, but they are situated in a certain context. Therefore, as artists, we are social beings whose knowledge and skills depends on the way in which we engage with our environments. Hence, our work, processes, thoughts, sensitivities and ideas should not be considered as isolated, but as highly situated. Therefore, we can benefit from becoming aware of our specific way of engaging with the world. This training works with the assumption that the way in which we move through, relate to and attune ourselves to our environment depends on the way in which we use our body. When performing our (artistic) practices, we always use our bodies (in certain ways and in others not). Hence, in order to sensitize and attune ourselves to our practice’s needs, we train our body awareness.

During our body work sessions we will explore our body as an “instrument”. Each student, each artist, each researcher is, has and does a unique instrument with which they sense, attune to and relate to the world. Our bodies are our means through which we gather and process information, move through our environments and produce work. In short: not only is our body always there with us; it is the very medium we do our work with. Therefore, we will work on becoming aware of our instrument, learning about its specificities, how we attune it to and how it is affected by our surroundings. We work on “calibrating” our instrument to the practices we perform, the spaces we move through and the contexts we work in.

Because these sessions combine bodywork with documentation and reflection, we will develop both intuitive and sensitive as well as analytical and reflective skills. We do this by building on the idea that finding words or other (e.g., visual) means to articulate what we perceive with our senses, helps to become even more sensitive (think of a wine taster who, by learning words for what she senses, learns to taste even more nuanced tastes). We will therefore practice documentation and teaching each other. Furthermore, while working on registering, documenting, articulating and presenting what bodies do, we work on making embodied and tacit forms of knowledge explicit (in order to enable exchange with other “wine-tasters” and establish ourselves within a “wine-tasting community”).

We can think about documentation like a process of wine-tasting. By learning words for what she senses, the wine-taster learns to taste even more nuanced tastes. Hence, finding words or other (e.g., visual) means to articulate what we perceive with our senses, helps to become even more sensitive, more body aware. Practicing documentation and reflecting together, we work on making embodied and tacit forms of knowledge explicit (in order to enable exchange with other “wine-tasters” and establish ourselves within a “wine-tasting community”).

Hence, even though tacit knowledge may be difficult to put into words - or is able to exist without words – we will learn from the attempts to articulate these kinds of knowledges, in words or otherwise. Building on the work of Stefan Hirschauer (‘Putting things into words Ethnographic description and the silence of the social’, 2006) Ruth Benschop writes:

“In order to talk about what does not present itself in language, the researcher has to take herself serious as research instrument. She makes use of her connectedness to the world. The non-verbal aspects of realtity are eminently the terrain of subjectivity, of the body and the senses. The body of the researcher is, through her private and precise preparations, receptive to the world she is part of. This is why observation is always also self-observation: the researchers can detect – smell, taste, feel, see – something in the words she researchers by attending to what she experiences herself.” (freely translated from Benschop’s “De Eland is een Eigenwijs Dier, 2015).

How to practice attentiveness? This is what we will explore in our classes and through this paper object.

This paper object will function as a tool for documentation. In a way, it is a research instrument in and on itself. Like the tasting wheel of a wine taster, it is not only a means to describe what you become aware of, it is also performative in producing awareness, or knowledge. It produces tacit knowledge, which it also helps to articulate.

Use the paper object all the time, not just when you work on body awareness. Using it in moments you do not work on body awareness, will help you work on body awareness in these moments. Unfold it, fold it, write, draw, paint, doodle, scribble, glue and collect in it. Make it your own. By the end of our journey, all of our paper objects will look and feel and tell us something completely different and unique. Our paper object will be as various as the bodies we practice.

The metaphor of the researcher as a sensitive research instrument has been used a lot in the research centre What Art Knows, see for instance the article “Drawing Instruments drawing instruments: About Drawing as a Method of Reflection”. Here, Veerle Spronck discusses how artist duo Dear Hunter use drawing as a method to research their own artistic practice. Each screw, each detail is there for a reason. By disassembling their own practice like that and assigning each part of the process a material representation they opened up their artistic process for themselves and others.

Link to Dutch article: DRAWING INSTRUMENTS DRAWING INSTRUMENTS, by Veerle Spronck.